The bonfire of vanities. A curial story.

The last document released by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace was delivered to the participants to G20. Some of the proposal contained in the document were also part of the agenda of the summit. For example the tax on financial transactions, called a “Tobin tax” after the name of its creator, or a “Robin Hood tax.” popped up in some of the comments of Barack Obama and Nicholas Sarkozy, even if nothing concrete was done about it. There was who, in the Vatican, disliked the document – better: disliked not to have been consulted during the preparation of the document, and complained for this to cardinal Bertone. The Secretary of State, in return, complained that he had not known about it until the last moment, decided to put the Curia under “lock and key” by requiring a control for all the documents that will follow. This is what some media reported a few days after the release of the document of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. A polemics fired by a few, but designed to several consequences.

The last document released by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace was delivered to the participants to G20. Some of the proposal contained in the document were also part of the agenda of the summit. For example the tax on financial transactions, called a “Tobin tax” after the name of its creator, or a “Robin Hood tax.” popped up in some of the comments of Barack Obama and Nicholas Sarkozy, even if nothing concrete was done about it. There was who, in the Vatican, disliked the document – better: disliked not to have been consulted during the preparation of the document, and complained for this to cardinal Bertone. The Secretary of State, in return, complained that he had not known about it until the last moment, decided to put the Curia under “lock and key” by requiring a control for all the documents that will follow. This is what some media reported a few days after the release of the document of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. A polemics fired by a few, but designed to several consequences.

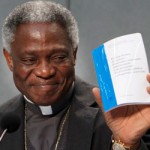

The document of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace is ponderously titled – «Towards reforming the international financial and monetary system in the context of global public authority» - and its remarks were the most specific. The Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace calls for the advent of a new world centered on a universal political authority. The idea is not unprecedented – it was previously evoked in the 1963 encyclical Pacem in Terris of John XXIII. The document also proposed taxation measures on financial transactions (and suggested that revenues could contribute to the creation of a “world reserve fund” to support the economies of countries hit by crisis); forms of recapitalization of banks with public funds that make support conditional on “virtuous” behavior aimed at developing the real economy; more effective management of financial shadow markets that are largely uncontrolled today. Such moves would be designed to make the global economy more responsive to the needs of the person, and – the document says – less «subordinated to the interests of countries that effectively enjoy a position of economic and financial advantage».

The path to the document had been long and transparent. In May, after a media briefing with journalists to announce a conference about the Mater et Magistra, mons. Mario Toso, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, announced the journalist that another media briefing was up to come, and it would have been about a future note for the reform of the monetary system. The Vatican Secretary of State was obviously informed. There had been several sketches of the document, as usual. The first sketch was drawn down by Michel Camdessus, former president of the International Monetary Fund, consultant of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and part of the French delegation at the last G20 meeting. Then, document passed through several hand, bankers like Antonio Fazio – former governor of the Bank of Italy – and Ignazio Musu – economist and part of the advisory board of the Bank of Italy. The document shields itself with many citations from previous social encyclicals, and actually there is nothing so new.

In the Caritas in Veritate there is also a paragraph – the so-called «world authority paragraph» – in which it is stated that

«in the face of the unrelenting growth of global interdependence, there is a trongly felt need, even in the midst of a global recession, for a reform of the United Nations Organization, and likewise of economic institutions and international finance, so that the concept of the family of nations can acquire real teeth. One also senses the urgent need to find innovative ways of implementing the Principle of the responsibility to protect and of giving poorer nations an effective voice in shared decision-making. This seems necessary in order to arrive at a political, juridical and economic order which can increase and give direction to international cooperation for the development of all peoples in solidarity. To manage the global economy; to revive economies hit by the crisis; to avoid any deterioration of the present crisis and the greater imbalances that would result; to bring about integral and timely disarmament, food security and peace; to guarantee the protection of the environment and to regulate migration: for all this, there is urgent need of a true world political authority. . . »

Even Caritas in veritate had been sketched by many hands. An encyclical is such an important text – it is addressed to all the men of good will, and it is inspiration and part of the diplomatic work of the Holy See – that everybody would like to stress it to its own part. Among the people that glossed the Caritas in veritate, there were economist like Stefano Zamagni and Luigino Bruni, but also the then governor of the Bank of Italy Mario Draghi and the then Italian minister of Economy Giulio Tremonti. Even Ettore Gotti Tedeschi had been involved in “glossing” the encyclical. He was still not president of the IOR (Institute for Religious Works), but he was already sure that the economical collapse came from the lack of children. No children, no creativity, no hope for the future, no economy: this simple four-words-speech-scheme is the Gotti Tedeschi’s favorite one.

After the release of the encyclical, there had been a sort of split on how to consider Caritas in veritate. Laissez-faire theorists were critical about some economical analysis, but always underlined how good was the “make more sons” line. Social economy theorists loved more the part that evoked the tunes of Populorum Progressio, the Paul VI social encyclical, in which the Pope claimed that «the new name of peace is development». The fight of interpretations was – and still is – intense. Ettore Gotti Tedeschi was invited to talk to the meeting about Caritas in veritate without either informing the Pontifical Council Justice and Peace. And the medias were in some way divided between these two lines of the encyclical, and were totally unaware that the truth is in the middle.

The most prophetical part of the encyclical was the so-called “world authority” paragraph. In fact, this has been interpreted by many Catholics a sort of “big leviathan”. But there is a deeper reason why the Holy See has been doing this proposal. And one can find these reason looking back in history to see when this world order had been stated. The Peace of Westphalia was a series of peace treaties signed between May and October of 1648 in Osnabrück and Münster. The treaties resulted from the big diplomatic congress, thereby initiating a new system of political order in central Europe, later called Westphalian sovereignty, based upon the concept of a sovereign state governed by a sovereign. In the event, the treaties’ regulations became integral to the constitutional law of the Holy Roman Empire. It was there that the Holy See began to the fight not to be ejected from the concert of nations. It was there that the Holy See became to be subjected to the secularizing process. An increasing lack of influence that brought the Vatican State to be attacked and then defeated by national States, and to sign agreements with the States – which are the various Concordats.

Peace of Westphalia is quoted in the last document released by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, and it is not a case. In the last years, many have talked about a New World Order. This new world order had been theorized in several think-tanks all over the world – from the Trilateral Commission to Bildeberg Group – and in the mean time finance prevailed on policy. The new world order will be an economic-based one. This seems to be the time for the change to come. So, while the Holy See was going on in signing Concordats with the national States, the world governance got always more supranational. The scenario is similar to the one of the Peace of Westphalia times. Within the Holy See, many are aware of the risk for the Church – and religions as well – to be put aside. This is the sense of the call for common rules and a world authority with universal competences.

When the document of Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace had been released, there had been a slight disagreement within the Vatican Curia. Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, president of the IOR, complained to have not been even consulted during the preparation of the document. No consulation was the fact that when one then delves into the analyses and specific proposals, it is also stunning how strong the divergence is between what is written in the document of the pontifical council for justice and peace and what has been maintained for some time in the financial commentaries published in L’Osservatore Romano by Ettore Gotti Tedeschi. For example, not even one line in the document attributes the global economic and financial crisis to the collapse in the birth rate and to the resulting higher and higher costs of population aging.

Gotti Tedeschi did not remain silent. On November 4 L’Osservatore Romano published an editorial by him that reads like a complete repudiation of the document of the Pontifical Council for justice and Peace. Gotti Tedeschi wrote that «the true origins of the collapse of birthrates and the consequences of the increase of taxes on the GDP to absorb the costs of the ageing of the population were wrongly interpreted. The effects of the decisions made to compensate for these phenomena were underestimated, especially with the de-localization of production and consumer debt». For the president of IOR, «to deflate the total debt – public, banking, business and family – and bring it back to pre-crisis levels, that is, to around 40% less, it is possible, though not advisable, to cancel a part of the debt with a type of “preventive agreement,” where creditors are paid at 60%».

More. Someone inside the Roman Curia – sources whisper that it was Gotti Tedeschi himself, very active indeed (he also wrote down an article for the Italian magazine Tempi) – complained about the document with the cardinal Bertone, secretary of State. Medias report that Bertone complained to have not been even informed by document. It was not true, since he had been constantly kept informed of the document. And this is what he said, sources from inside the Curia report. Probably, the truth is in the middle: pressed by the vain discontents memeber of the Curia that were protesting, Bertone said that he knew about the document, not about his contents, and he managed a summit to solve the question. The news about a summit convened in the Secretariat of State on November, 4th leaked to the press. The conclusion of the summit was that this binding order would be transmitted to all of the offices of the curia: from that point on, nothing in writing would be released unless it had been inspected and authorized by the Secretariat of State.

This is how the red alarm for the new document of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace has been defused. In the mean time, very few know about the international activities of the Holy See, and the financial transparency brought on with the establishment of the Authority for Financial Information can have some contraindication. The game is on the international impact of the Holy See. The same game the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace played by asking for an World Authority with Universal Competences. Since the world is now globally ruled, the Holy See want to give is contribution to write common rules. In order these common rules will be for the common good of humanity, and not just for the good of few. Will this commitment be consumed in the bonfire of vanities?